May 13, 2020

Safer “Re-Opening” for High Risk Workers & Households

Here is my current thinking about the public health implications of focusing exclusively on protective practices at work to manage the threat of COVID-19 in the workplace. Return-to-work plans really must be individualized — and doing so will save lives. In fact, the plans should be stratified by level of risk in three areas:

- the risk of exposure to the coronavirus posed by each worker’s specific job tasks / work environment; and

- the worker’s individualized risk of COVID-related death if they get infected; and

- their whole household’s risk of death if they get infected — because workers who do acquire infection at work will take it home.

Protective measures such as altered work practices, personal protective equipment, and so on are unlikely to be 100% effective due to transmission of the virus by people without any signs of illness. (Think of the asymptomatic but infected White House staffers who exposed others — despite daily testing). Some infected but asymptomatic workers may spread the coronavirus at work. The workers who catch it may be young and healthy, developing only mild illness. But there may be vulnerable family members or caregivers in their homes for whom infection then proves fatal. Other workers may be at much higher risk for a poor outcome due to a personal vulnerability, becoming critically ill or even dying from COVID-19.

Can we all agree that one of our major goals is to minimize preventable COVID-19-related deaths? We should be encouraging, incentivizing, or even requiring employers to make accommodations based on each worker’s total level of risk (level of exposure + personal risk factors + household members’ risk factors). And ideally those accommodations will include NOT returning workers at high risk to the physical workplace until all the kinks have been worked out and enough time has passed to assure all parties that COVID-19 is not being passed around among the workers.

Many local governments are allowing business re-opening to proceed without much articulation of the PRINCIPLES that should guide the re-opening. In my opinion, they should be explicitly advocating for an approach that appropriately considers and balances FOUR THINGS:

- The importance of an industry or type of business to the well-being of the community;

- Risk of exposure for the public during business operations – the customers of the businesses;

- Risks of exposure to workers due to the inherent nature of the tasks and/or the built work environment – which sometimes cannot be eliminated entirely;

- The vastly different consequences of infection, especially variability in the likelihood of critical illness and death, among various subgroups of the workforce (and the population as a whole).

Let’s start with a recap: Why was everyone requested/required to shut their businesses, stay home, practice social distancing, and wear PPE or face coverings in the first place? I believe it was:

- To prevent unnecessary and excessive deaths by reducing contagion at work OR via community spread — in an effort to avoid overwhelming the health care system, especially with critically-ill and ventilator dependent patients;

- To give the “experts” enough time to study the behavior of the virus / illness / pandemic and learn essential facts to guide future action in a wise direction.

By making the decision to reopen society, powerful people have silently made the decision to allow community infection to spread — at a measured pace — as the only practical way to achieve the herd immunity required to end this pandemic and social paralysis in less than a year. I actually agree that this is the best alternative we have. A vaccine is unlikely to be available quickly enough or be sufficiently effective to do it.

However, we MUST do it in the least dangerous/destructive way. We should allow infection to spread among the low risk part of the population WHILE EFFECTIVELY PROTECTING the high risk segments. Once a sufficient number of low risk households have become immune, they then become the “herd” that surrounds and protects the vulnerable subset which has not yet aquired immunity.

Personally, I find totally repugnant the argument that “business necessity” allows government and employers to turn a blind eye to the reality that exposure of Mama or Daddy at work can lead to death to Grandma, Granddaddy, or the chronically ill child back at home.

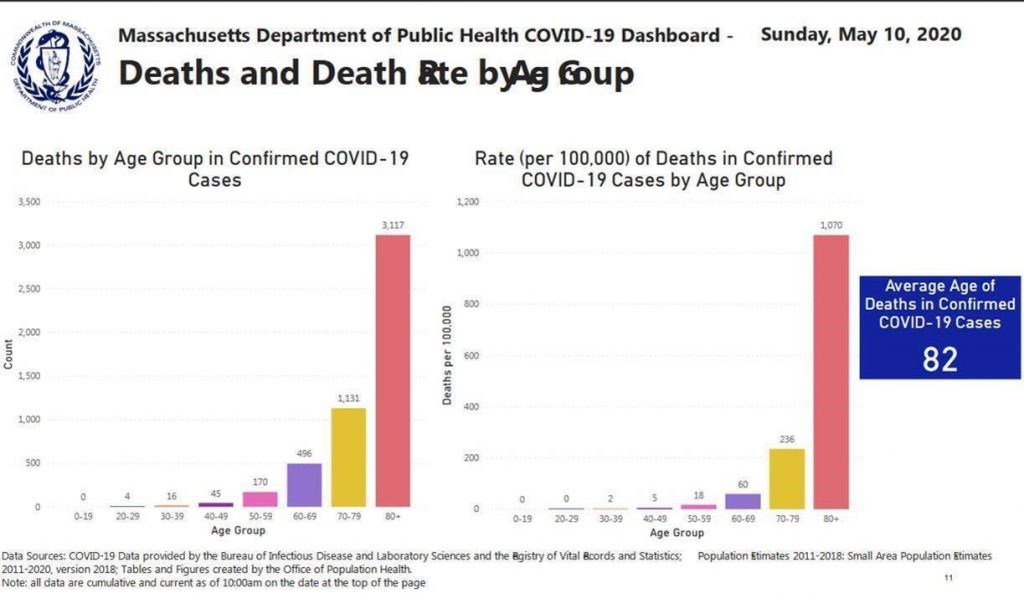

Over the last few weeks, the stark disparity in level of risk of death by age decile has become more and more apparent. Likewise, the specific comorbidities that increase risk have been increasingly sharply defined. That means we NOW HAVE the INFORMATION needed to STRATIFY RISK and should act accordingly. Here’s some key data from the Massachusetts COVID-19 dashboard as of May 10. (See the charts on pages 12 and 13 – which are also pasted below.)

- Low risk of death: From ages 0-29 the risk is ZERO per 100,000, between the ages of 30-30 is 2 / 100,000, and age 40-49 is 5 / 100,000

- Higher risk of death: age 50-59 is 18 / 100,000; age 60-69 is 60 / 100,000

- HIGH risk of death: age 70-79 is 236 / 100,000; age 80+ is 1070 / 100,000

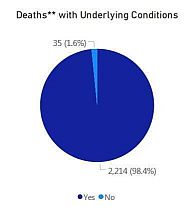

Virtually all of the deaths in Massachusetts — 98.4% — have occurred in cases where there was a pre-existing underlying risk — at least one of the conditions associated with fatal outcomes, including age. This data is based only on deaths for which investigations have been completely — somewhat more than half.

The R0 (risk of spread) is highest within households, with a secondary attack rate of 10% to 19%. In fact, the majority of all COVID-19 cases have been due to household spread.

o https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/8/20-1274_article

o https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa450/5821281

o https://www.contagionlive.com/news/spouses-adults-covid-19-infection-household-member

o https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423v1.full.pdf

o https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.11.20056010v1

I’m not arguing that employers should make invasive and potentially illegal inquiries into each worker’s health status and living situation – but rather that employers should be making accommodations to protect workers who are in a high risk category either because of their own risks or those in their household. And workers should have the RIGHT to refuse to work if they or their family members are actually at high risk without fear of losing their jobs – sort of like the FMLA.

So, for example, how about instituting these THREE steps at the employer’s front door on Day 1: (1) temperature; (2) symptom inquiries / questionnaire; (3) a very short and confidential risk screening questionnaire.

“Yes” answers on the symptom and/or risk screening questionnaires would then require a confidential (onsite or virtual) interview by a professional with medical training, possibly followed by a request for corroborating medical records or other documentation. Some medical expertise is required to evaluate and determine whether the risk is legitimate/realistic and to provide appropriate counseling. If risk factors are confirmed, counseling would be done according to a protocol. In a voluntary program, the counseling would prepare the worker to make a fully informed choice whether to reveal the risk to the employer and request an accommodation if necessary. In a mandatory program, the medical person would send a simple note certifying that “extraordinary precautions or other accommodations are warranted” or similar.

During the large scale return-to-work processes now getting underway, a key group is without any protections: people who feel well enough to work at the moment but are at unusually high risk for death in the event they DO get sick or injured. They are going to fall between the cracks of the social systems designed to protect sick, injured and disabled workers and their households. Employers have NO DUTY under OSHA to protect worker’s families (“the public”) from harm when workers acquire contagious diseases at work. In addition, no job / income protection will be available via either workers’ compensation, or commercial disability insurance or FMLA — because an “at risk” employee has no diagnosis/ no illness keeping them from working (yet). Those protections only begin once the horse is out of the barn. A grieving family’s only recourse will be the tort system, and the Congress or state legislatures may well pass a law relieving the employers from even that liability. And I seriously doubt that being currently able to function but at high risk for death if infected with this particular virus would qualify one as a person with a disability.

I guess my real beef is with overly-simplistic thinking at all levels of our government with regard to plans for the re-opening phase. I hope that occupational medicine physicians who have the ear of the public health authorities in their states will raise this issue loudly. Everyone needs to sit around a table and figure out how to INTELLIGENTLY open business AND allow workers to protect themselves and their vulnerable family members at THE SAME TIME.

Surely, creative thinkers in combination with expert science communicators and practical program designers should be able to team up, figure out a good way to do this, then request a hearing with people in power — and proopse a comprehensive re-opening plan that makes good sense from BOTH a public health AND an economic perspective!